Colonial art, which represents the early visual culture of the New World, holds a unique position as a bridge between European artistic traditions and the fresh experiences of American colonists and native populations. One of the earliest examples of this hybrid is Theodore de Bry’s Voyages en Virginie et en Floride (1591), a Flemish printmaker’s collection of engravings that gave Europe its first glimpse of America through the eyes of artists who had witnessed it firsthand.

De Bry’s engravings were based on paintings by two key figures: John White and Jacques Le Moyne. Their depictions of the native peoples and landscapes of America played an integral role in the European perception of the New World. While these works introduced a new subject matter — the indigenous peoples of America — the artistic style remained distinctly European. Both artists worked within the European mannerist tradition, which emphasized exaggerated, distorted, and anti-classical elements that had emerged during the late Renaissance. As Mooz puts it, this art was “European art carried as cultural baggage to the New World.”

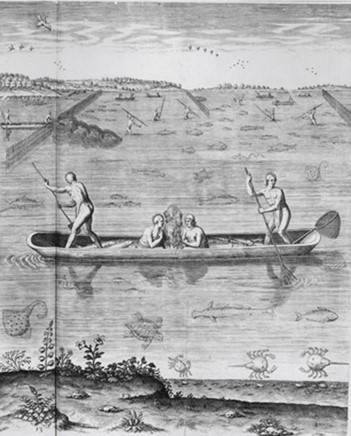

1. John White: “Their Manner of Fishynge in Virginia” (1585)

John White’s painting Their Manner of Fishynge in Virginia (1585), now housed in the British Museum, presents a scene of Native Americans fishing. White’s work was pivotal for the European understanding of the New World, capturing both everyday activities and the foreign nature of the indigenous peoples. Yet, despite its subject, the painting’s composition adheres to European traditions. Specifically, White’s style draws on northern, late-medieval elements, particularly the bird’s-eye view, a technique common in the Gothic tradition. White embraced this approach, utilizing multiple perspectives in a single painting, a trait that contrasts with the Renaissance focus on logical spatial coherence.

For instance, White’s fish, both in the foreground and background, are depicted as the same size. This disregard for scale and spatial logic evokes Romanesque miniatures, which rejected the Renaissance ideal of creating a realistic, perspectival space. In his work, White anticipates the more pictorially focused approaches of later artists, such as Jacques Callot, whose work emphasizes visual storytelling rather than strict adherence to symbolic forms or rational spatiality.

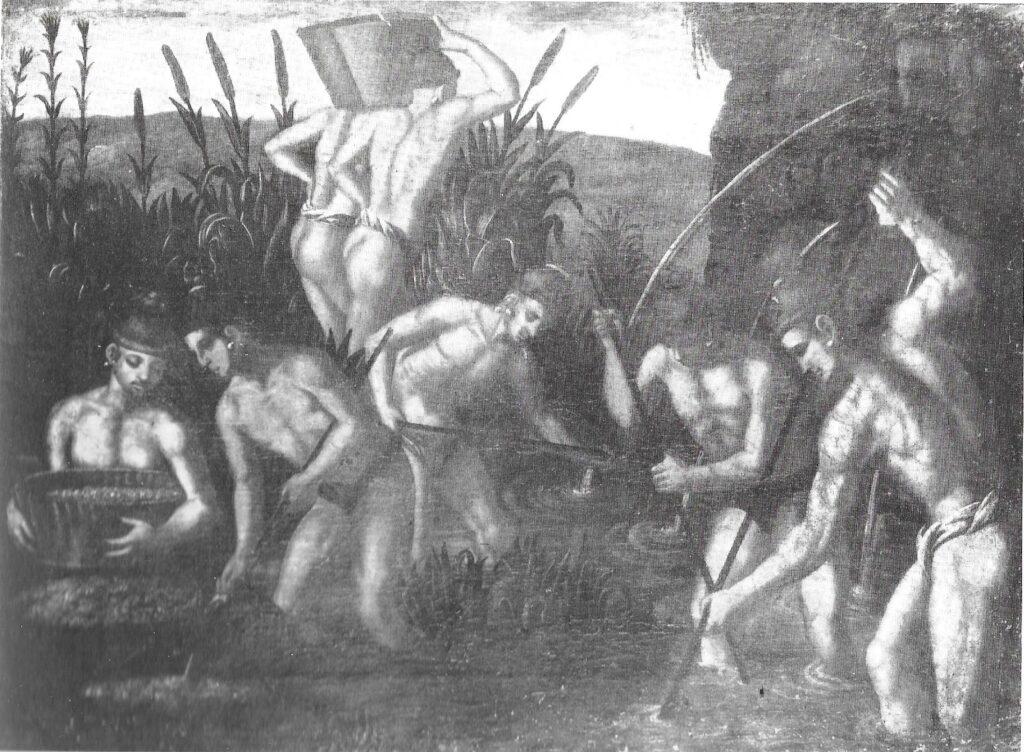

2. Jacques Le Moyne: “Indians of Florida Panning Gold” (c. 1564)

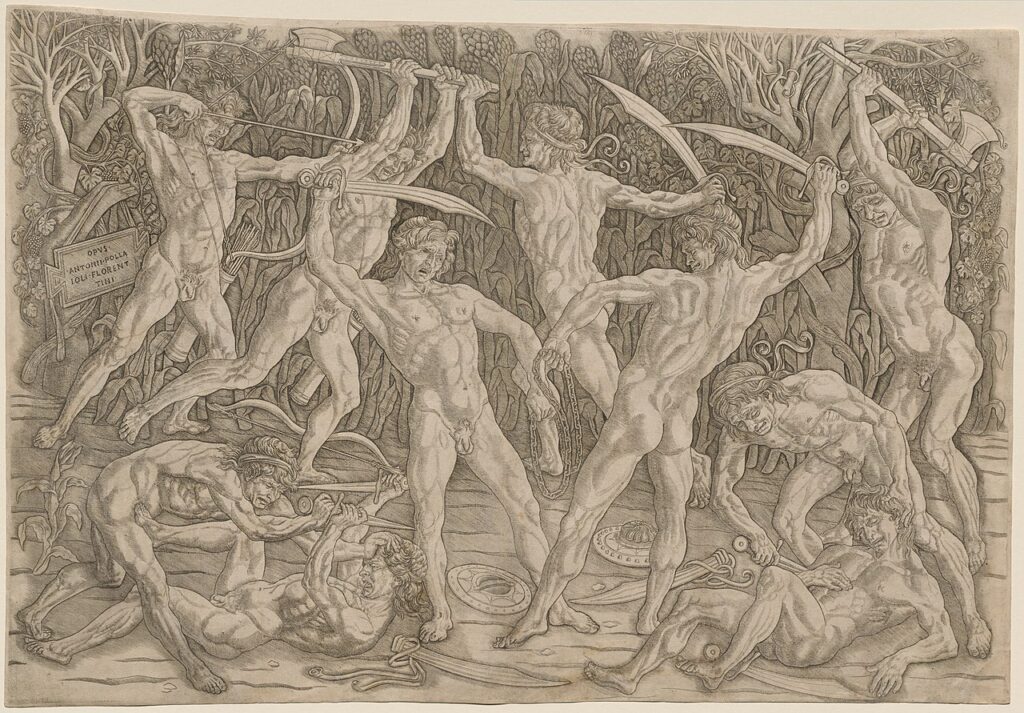

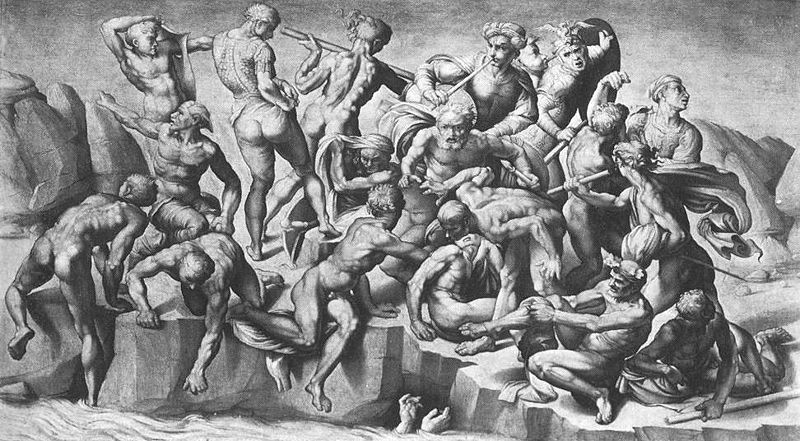

Le Moyne’s Indians of Florida Panning Gold (c. 1564) offers another glimpse into the European portrayal of Native Americans. Created earlier than White’s work, Le Moyne’s painting is now preserved by Dawsons of Pall Mall in London. Unlike White, Le Moyne depicted the human figure through the established lens of Renaissance art. His stylistic choices have been linked to Pollaiuolo’s Battle of the Naked Men (c. 1470) and Michelangelo’s drawing for the Battle of Cascina (1504), both of which feature dynamic compositions of the human body in action. Le Moyne’s rendering of the Native Americans engages this same tradition, merging New World content with Old World form.

Like White, however, Le Moyne was more interested in the pictorial representation of a scene than in its symbolic significance. His figures are rendered in a manner that demonstrates an understanding of anatomy and motion, reflecting the Renaissance’s obsession with the human form. Yet, despite this connection to the Renaissance, the portrayal of Native Americans remains filtered through a European lens, with an emphasis on their “exotic” nature.

European Mannerism and its Influence

The art of both White and Le Moyne is deeply rooted in European mannerism, which was defined by its departure from classical Renaissance ideals. Mannerism is characterized by a heightened emphasis on the strange, the exaggerated, and the unusual, rejecting the harmonious proportions and balanced compositions of the High Renaissance. This is evident in both artists’ work: White’s disregard for logical space and Le Moyne’s adoption of the traditional Renaissance motif of the human figure are both tinged with a sense of the unfamiliar and the chaotic.

Mannerism itself was shaped by tensions between control and chaos, deriving from the broader artistic dichotomy between Italian idealism and Northern European naturalism. While Italian art sought to impose an idealized, almost abstract vision of human figures and landscapes, Northern European art was more concerned with the detailed depiction of nature and everyday life. Both White and Le Moyne navigated this tension in their depictions of Native Americans — subjects who were, to European eyes, both real and symbolic of the strangeness of the New World.

The Intersection of Two Worlds

In conclusion, the colonial art depicted in Voyages en Virginie et en Floride encapsulates the intersection of European artistic traditions and the new realities of the American colonies. John White’s bird’s-eye views and disregard for rational space contrast with Jacques Le Moyne’s more traditional Renaissance human figures, yet both artists worked within the broader framework of European mannerism. While their subject matter was uniquely American — portraying indigenous peoples and landscapes never before seen by European eyes — their style remained firmly rooted in the traditions of European art.

Summary for Memorization (PassNotes):

- Theodore de Bry: Flemish printmaker, created Voyages en Virginie et en Floride (1591) with engravings depicting the New World.

- John White: Their Manner of Fishynge in Virginia (1585, British Museum). Northern medieval style, bird’s-eye view, disregards logical space. Linked to Romanesque miniatures. Preceded Jacques Callot’s pictorial focus.

- Jacques Le Moyne: Indians of Florida Panning Gold (1564, Dawsons of Pall Mall). Renaissance human figure tradition. Stylistic antecedents: Pollaiuolo’s Battle of the Naked Men and Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina.

- Mannerism: Both artists depicted Native Americans through European mannerism — exaggerated, unusual, anti-classical — blending control and chaos in tension with Northern naturalism and Italian idealism.

The print of Battle of the Nudes in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art is the only known first-state impression of the piece.

The Battle of Cascina is a painting in fresco commissioned from Michelangelo for the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. He created only the preparatory drawing before being called to Rome by Pope Julius II, where he worked on the Pope’s tomb; before completing this project, he returned to Florence for some months to complete the cartoon